My Favourite Paintings from History (part one)

"Look Papa, Bulls!"

This is not meant to be a comprehensive history of animals in art. It's just a few of my own favourite periods and paintings. I wouldn't claim to be an expert on art or animals, but as a pet portrait artist and the owner of three dogs, I have more than a passing interest in the subjects. Animals have been a subject for artists since men first began to paint. The first known examples date back at least 17000 years. When the cave paintings of Altamira, in northern Spain came to light they were, quite literally a revelation. Nobody had any idea that our ancestors were capable of producing the kind of work that was revealed in the caves. The Altamira paintings were discovered in 1879 by a little girl called Maria. Her father was a Spanish nobleman and an amateur archeologist. One day he was looking for pre-historic tools that he thought might have been abandoned on the floor of the cave, thousands of years ago. He'd brought his small daughter along with him, and she was getting bored. Maria happened to glance up at the ceiling. "Look Papa", she said, "Bulls!"

It was not until 1903, long after the Don's death, that a young French priest called Henri Breuil began making copies of the paintings. Up until then academics had thought the paintings could be no more than 20 years old. Gradually the world became aware of the treasures in the cave.

Even more famous are the cave paintings which were found at Lascaux in the south of France in 1940. When Picasso first saw them he said, "We have learned nothing", and when you see this horse, (right) and the many others like it, you can see exactly what he meant. The beauty of it, the strength, the grace and the knowledge that the artist obviously had, are astounding. It is a true work of art. The artist lives in the same world as the horse, and yet he can be detached enough to observe it, and to comment on it. This is all the more remarkable when you consider that man was not the all-powerful 'lord of creation' that he likes to think he is today. He was a weak, vulnerable creature who, like a Mississippi gambler, survived on his wits. There is no doubt in my mind that these early men, fully integrated into the natural world as they were, already knew that they were somehow apart from it. Not yet able to control their environment in any significant way, they could still record images from their life on the walls of the cave, as in this painting of a horse from the Lascaux Cave.

Cave painting of a horse

Here are two more paintings by the master of the Lascaux cave. I don't think the spontaneity and energy in this picture of a horse (left) has been bettered in any art since.

In this picture (below) a man is being attacked and probably killed, by a bison. There are caves containing, not art but human skulls with teeth marks that correspond to the teeth of a leopard or a lion. Life, death, art and survival were all on the same wheel in those early days.

We tend to imagine the early artists as solitary figures, scratching away at a rock surface, but that is not how it was. The artist would have been the head of a dedicated team. It might even be appropriate to think in terms of a studio not unlike Michaelangelo's. There was nothing amateurish in the operation. Each of his assistants would have had his own task - mixing the various paint materials, taking care of the brush tools or holding up a torch for the artist. The master would have been on a platform which was supported by scaffolding, perhaps held in place by assistants. Sockets for the scaffolding have been found cut into the walls, along with pestles and mortars in which colours were mixed.

Cave water, vegetable and animal oils were used as binders. Primitive crayons have been found. Paint was applied with brush tools or was sprayed on with blow pipes. Colours used were red, red ochre, black, white, yellow and brown.

The Magdalenian art system, the first and by far the longest in the history of art, finally came to an end about 12000 years ago, as the cool, near-glacial climate warmed, and humans and animals began to change their way of life.

The end of the ice age made agriculture possible, which in turn made it possible for complex cultures to flourish. One of the earliest and most enigmatic was the Ancient Egyptian civilization. I have to admit that I don't much warm to Ancient Egyptian art. I find it rather rigid and oppressive - perhaps you had to be there. But I do like these two paintings.

On the left is a tomb painting of a man named Ipy and his dog called (by me) Pippa.Ipy is busy drawing water from the Nile. I imagine Pippa is trying to help, but in the age-old way of all dogs, is just getting in the way...

(below)The Ancient Egyptians adored cats - worshipped them in fact... I couldn't resist including this painting. It is, of course a modern image, but I feel the ancient world would have instantly understood and approved.

Modern Egytian painting, woman and cat

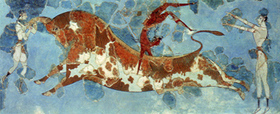

The next two frescoes are from the Palace of Knossos, in Crete. For a long time Crete was the

centre of the Minoan civilization.

I'm sure they know what they are doing in this panel below, but it looks dangerous to me.

(Below right)This panel features Dionysos, son of Zeus, sitting on a panther. I hope he knows what he is doing, too.

Ancient Greek wall painting

Ancient Greek wall painting

By 200 BC Rome was becoming the dominant force around the Mediterranean. Although they were great soldiers and engineers, the Romans were not so well-known for their artistic abilities. They borrowed many of their ideas from the Greeks. We know they could be very cruel to animals (and people), but these four charming pictures show, I think, a different side of the Roman character. The first two are mosaics. The dog on the lead is full of energy but probably knows how to sit and roll over, and in the second image, could there be a more affectionate portrayal of the relationship between a boy and his dog? The closely observed fresco of the nightingale, found at Pompeii and the image of waterbirds and a crocodile show a closeness to nature which we can perhaps envy.

James Collins Scottish Essays

Go to Favourite Painters (part two)